All writing

Blockchains in Africa

crypto

When 96% of citizens can't access the solution

3 min readMay 22, 2022

In 2022, the Central African Republic adopted Bitcoin as legal tender. 4% of its population has internet access.

Who benefits from Bitcoin adoption in a country where 96% of citizens can't use it?

This question captures the gap between crypto's promise in Africa and its practical reality. The continent faces problems blockchains could genuinely solve—currency instability, remittance extraction, limited financial access. But "could solve" and "will solve" are separated by infrastructure, education, and political reality.

The Landscape

Over 1.5 billion people live across Africa's 54 countries, about 40% under age 15. Nigeria, Seychelles, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, South Africa, and Tanzania are all experimenting with blockchain in different ways—some through policy, some through partnerships, some through grassroots adoption.

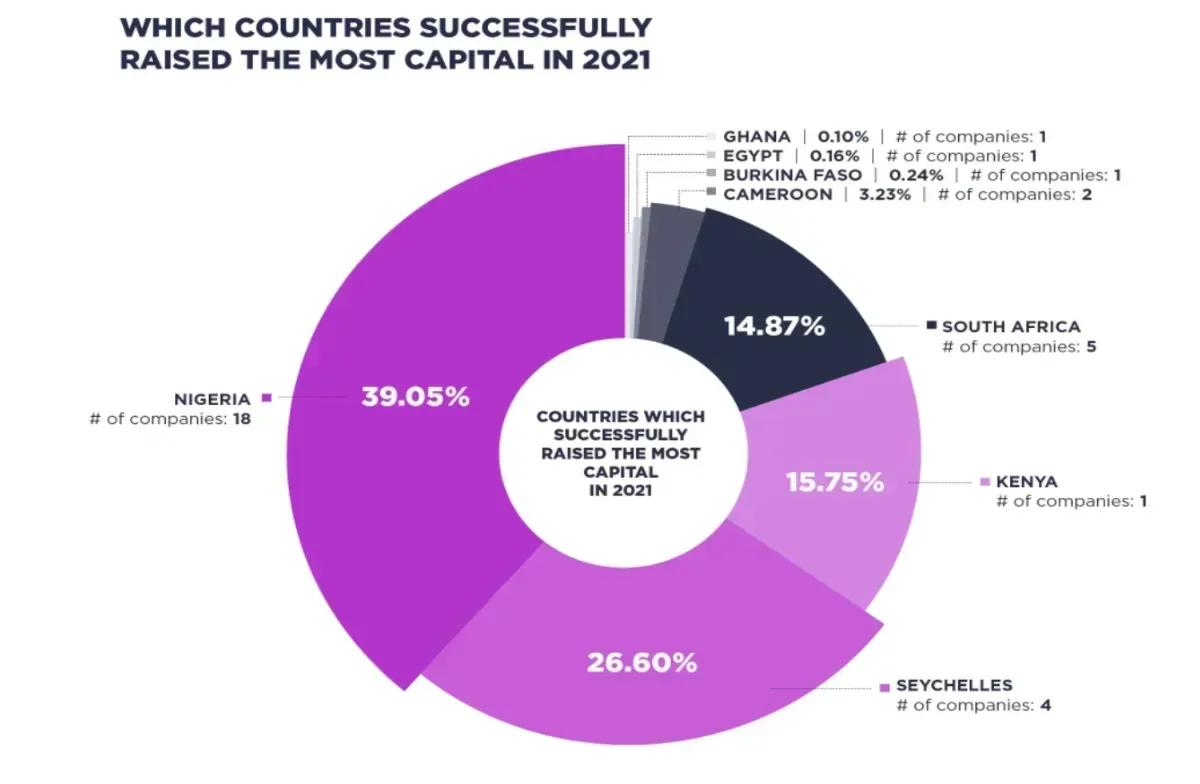

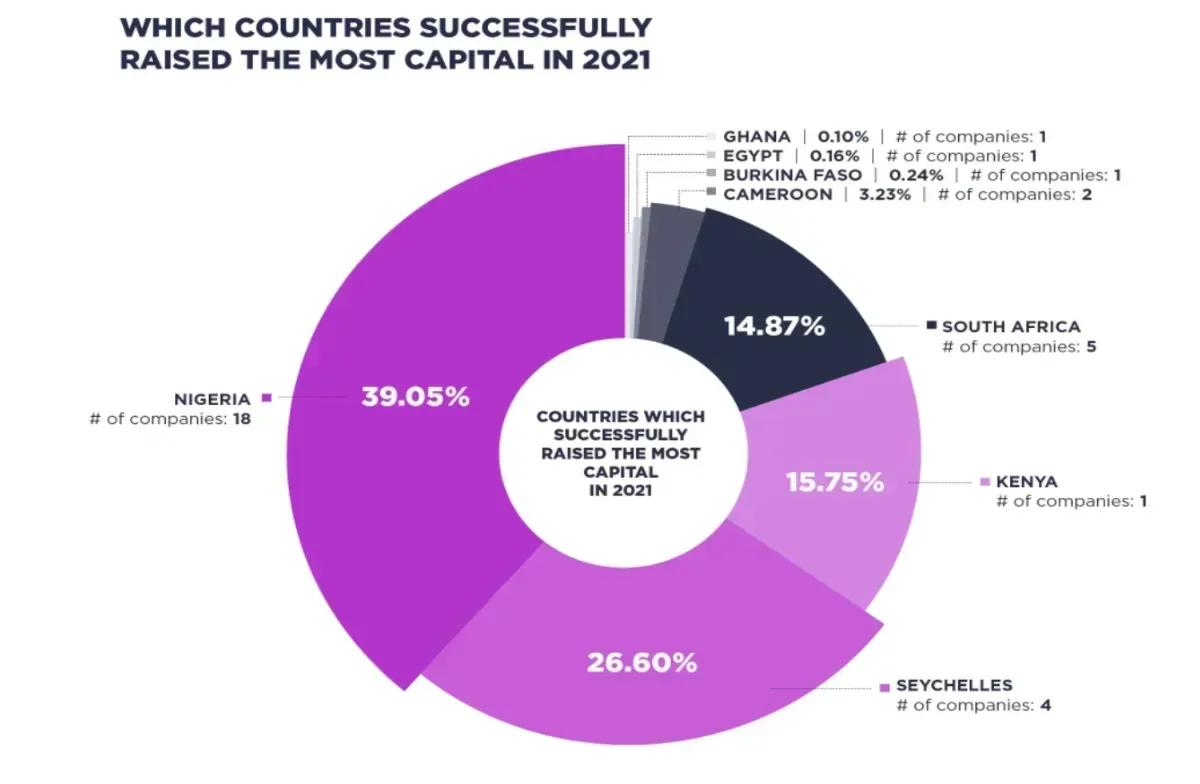

Nigeria and Seychelles have captured over half of all blockchain VC funding on the continent. The contrast within Nigeria alone tells the story: millionaire population up 44% in a decade, yet nearly 60% live on less than $1 per day. Crypto isn't solving inequality. But it might solve specific problems for specific people.

What Blockchains Could Actually Help With

Currencies

Many African currencies suffer from chronic inflation. Zimbabwe's 2007 hyperinflation reached the point where prices doubled every 24 hours. The South African Rand has lost significant value in recent years. For individuals and businesses, this makes it nearly impossible to store value or transact reliably.

Stablecoins like USDC and USDT, accessible via non-custodial wallets, let users hold assets in more stable units without depending on fragile local banks.

Remittances

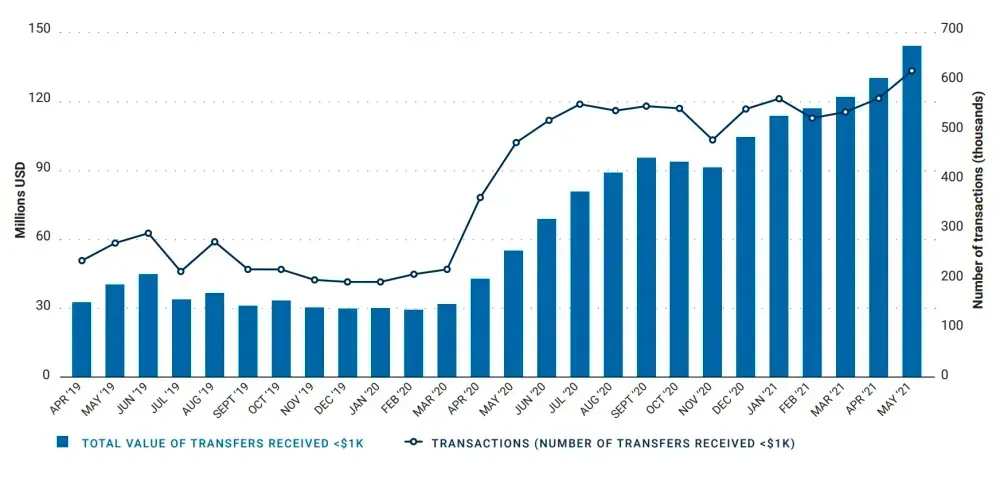

Workers abroad sending money back to families at home get crushed by fees. In 2024, remittances to low and middle-income countries reached $685 billion—up 47% from $466 billion in 2017.1 The global average fee has declined to 6.49%, down from 7.45%—but that still means approximately $44 billion extracted annually.2

For perspective: $44 billion exceeds the entire US non-military foreign aid budget. It's not redistributing wealth—it's extracting from people who can least afford it.

For a typical worker, that 6.49% means roughly 24 days of labor per year just to move money home.

On Solana, you can send a million transactions for around $10. The technology works. But local banks often don't accept crypto, regulators are skeptical, and off-ramps are limited. The last mile is the hard mile.3

Debt and Digital Sovereignty

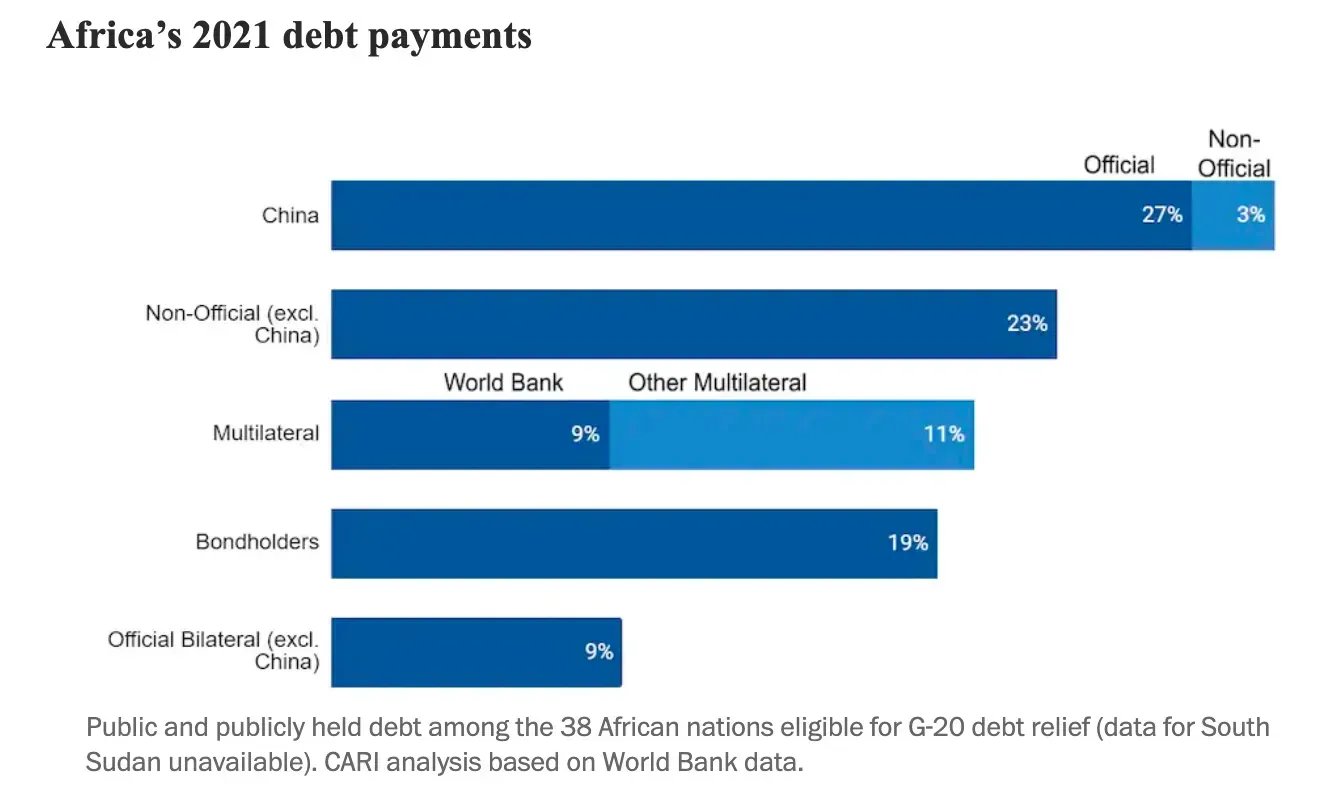

China is now Africa's largest creditor and has banned public crypto use at home to make way for its central bank digital currency.

Over the past two decades, China has invested heavily in African infrastructure—roads, railways, ports. These projects come with long-term debt obligations that limit recipient countries' independence.

Blockchains offer a potential alternative: African businesses and individuals operating globally, raising capital, storing value—without relying on local banks, fragile currencies, or permission from centralized authorities.

When Adoption Goes Wrong

The missteps are instructive.

El Salvador (2021): Made headlines adopting Bitcoin as legal tender. Despite early fanfare, the Lightning Network struggled with adoption, vendor resistance remained high, and the IMF downgraded the country's credit rating.

Central African Republic (2022): Followed suit with Bitcoin adoption. The context matters: 4% internet access, ranking 188 out of 189 on the global welfare index, deep ties to Russia, long-standing instability.

Even the optimistic take—"Now citizens won't need to carry CFA francs to convert into dollars!"—misses the prerequisites. You need reliable internet. You need to understand how any of this works. You need enough savings to absorb network fees that can exceed a month's income.

Announcing Bitcoin adoption is easy. Building the infrastructure and education for it to matter is hard.

Where This Actually Stands

In places like CAR, paying $5-15 in Bitcoin fees isn't practical when that's a month's income. It's not a solution—it's regression.

Low-fee chains like Solana make more sense for emerging markets. But even then, you need internet access, enough crypto literacy to not get scammed, savings to absorb fees, and off-ramps that actually work. For most of the continent, those prerequisites aren't met yet.

The problems are real. The solutions exist. The gap between them is infrastructure and education and time—not technology. Blockchains can help Africa, but only where the ground is ready. Everywhere else, it's waiting.

Footnotes

-

World Bank Remittance Prices Worldwide database and KNOMAD (Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development), 2024. Sub-Saharan Africa received approximately $54 billion in remittances in 2024, making it the fastest-growing region for remittance inflows. ↩

-

World Bank "Remittance Prices Worldwide" Q4 2024. While the global average is 6.49%, Sub-Saharan Africa remains the most expensive region at 7.73% average—still down from 9.4% in 2017. The UN Sustainable Development Goal target is 3% by 2030. ↩

-

The "last mile" problem in crypto remittances involves converting digital assets to local currency. Mobile money platforms like M-Pesa (290+ million users across Africa) represent potential integration points, but regulatory frameworks vary dramatically by country. ↩

Blockchains in Africa

crypto

When 96% of citizens can't access the solution

3 min readMay 22, 2022

crypto

In 2022, the Central African Republic adopted Bitcoin as legal tender. 4% of its population has internet access.

Who benefits from Bitcoin adoption in a country where 96% of citizens can't use it?

This question captures the gap between crypto's promise in Africa and its practical reality. The continent faces problems blockchains could genuinely solve—currency instability, remittance extraction, limited financial access. But "could solve" and "will solve" are separated by infrastructure, education, and political reality.

The Landscape

Over 1.5 billion people live across Africa's 54 countries, about 40% under age 15. Nigeria, Seychelles, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, South Africa, and Tanzania are all experimenting with blockchain in different ways—some through policy, some through partnerships, some through grassroots adoption.

Nigeria and Seychelles have captured over half of all blockchain VC funding on the continent. The contrast within Nigeria alone tells the story: millionaire population up 44% in a decade, yet nearly 60% live on less than $1 per day. Crypto isn't solving inequality. But it might solve specific problems for specific people.

What Blockchains Could Actually Help With

Currencies

Many African currencies suffer from chronic inflation. Zimbabwe's 2007 hyperinflation reached the point where prices doubled every 24 hours. The South African Rand has lost significant value in recent years. For individuals and businesses, this makes it nearly impossible to store value or transact reliably.

Stablecoins like USDC and USDT, accessible via non-custodial wallets, let users hold assets in more stable units without depending on fragile local banks.

Remittances

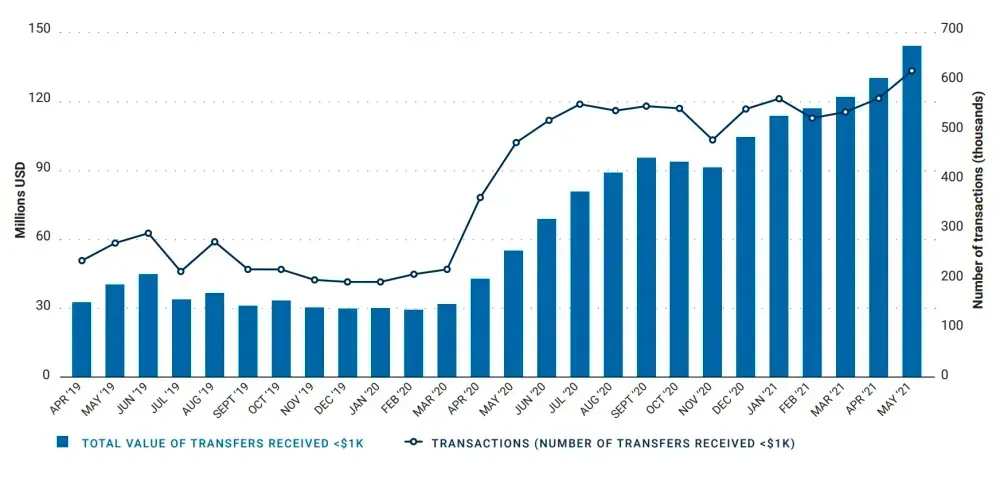

Workers abroad sending money back to families at home get crushed by fees. In 2024, remittances to low and middle-income countries reached $685 billion—up 47% from $466 billion in 2017.1 The global average fee has declined to 6.49%, down from 7.45%—but that still means approximately $44 billion extracted annually.2

For perspective: $44 billion exceeds the entire US non-military foreign aid budget. It's not redistributing wealth—it's extracting from people who can least afford it.

For a typical worker, that 6.49% means roughly 24 days of labor per year just to move money home.

On Solana, you can send a million transactions for around $10. The technology works. But local banks often don't accept crypto, regulators are skeptical, and off-ramps are limited. The last mile is the hard mile.3

Debt and Digital Sovereignty

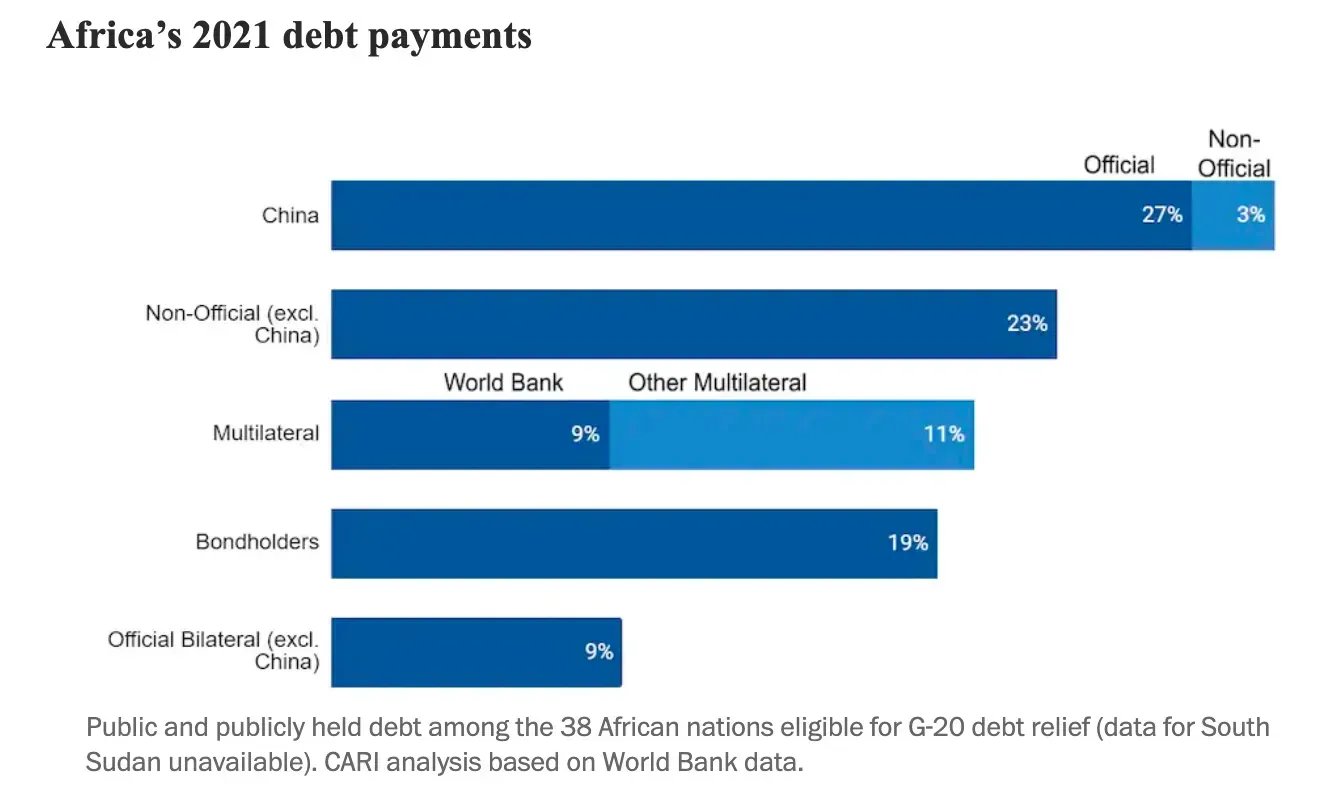

China is now Africa's largest creditor and has banned public crypto use at home to make way for its central bank digital currency.

Over the past two decades, China has invested heavily in African infrastructure—roads, railways, ports. These projects come with long-term debt obligations that limit recipient countries' independence.

Blockchains offer a potential alternative: African businesses and individuals operating globally, raising capital, storing value—without relying on local banks, fragile currencies, or permission from centralized authorities.

When Adoption Goes Wrong

The missteps are instructive.

El Salvador (2021): Made headlines adopting Bitcoin as legal tender. Despite early fanfare, the Lightning Network struggled with adoption, vendor resistance remained high, and the IMF downgraded the country's credit rating.

Central African Republic (2022): Followed suit with Bitcoin adoption. The context matters: 4% internet access, ranking 188 out of 189 on the global welfare index, deep ties to Russia, long-standing instability.

Even the optimistic take—"Now citizens won't need to carry CFA francs to convert into dollars!"—misses the prerequisites. You need reliable internet. You need to understand how any of this works. You need enough savings to absorb network fees that can exceed a month's income.

Announcing Bitcoin adoption is easy. Building the infrastructure and education for it to matter is hard.

Where This Actually Stands

In places like CAR, paying $5-15 in Bitcoin fees isn't practical when that's a month's income. It's not a solution—it's regression.

Low-fee chains like Solana make more sense for emerging markets. But even then, you need internet access, enough crypto literacy to not get scammed, savings to absorb fees, and off-ramps that actually work. For most of the continent, those prerequisites aren't met yet.

The problems are real. The solutions exist. The gap between them is infrastructure and education and time—not technology. Blockchains can help Africa, but only where the ground is ready. Everywhere else, it's waiting.

Footnotes

-

World Bank Remittance Prices Worldwide database and KNOMAD (Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development), 2024. Sub-Saharan Africa received approximately $54 billion in remittances in 2024, making it the fastest-growing region for remittance inflows. ↩

-

World Bank "Remittance Prices Worldwide" Q4 2024. While the global average is 6.49%, Sub-Saharan Africa remains the most expensive region at 7.73% average—still down from 9.4% in 2017. The UN Sustainable Development Goal target is 3% by 2030. ↩

-

The "last mile" problem in crypto remittances involves converting digital assets to local currency. Mobile money platforms like M-Pesa (290+ million users across Africa) represent potential integration points, but regulatory frameworks vary dramatically by country. ↩